See also: BOOKS / TRANSLATIONS / RESOURCES

Trudy has betrayed her husband, John. She's still in the marital home -- a dilapidated, priceless London townhouse -- but John's not here. Instead, she's with his brother, the profoundly banal Claude, and the two of them have a plan. But there is a witness to their plot: the inquisitive, nine-month-old resident of Trudy's womb.

Told from a perspective unlike any other, Nutshell is a classic tale of murder and deceit from one of the world's master storytellers.

To be bound in a nutshell, see the world in two inches of ivory, in a grain of sand. Why not, when all of literature, all of art, of human endeavour, is just a speck in the universe of possible things.

Editions

London: Jonathan Cape, 2016.

London: London Review Bookshop Limited Edition, 2016.

New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2016.

Knopf Canada, 2016.

Christopher Beha Introduces Ian McEwan and Nutshell at the 92nd St Y, September 2016

One of the best running jokes in Ian McEwan’s very funny new novel, Nutshell, involves a character whom the narrator calls “the owl poet,” because her entire literary output consists of poems about owls. “Certain artists in print or paint flourish in confined spaces,” the narrator explains in her defense. Part of the joke here has to do with the narrator’s own condition—about which more in a moment—but I also read in it a sly self-referential authorial wink. Over a long and distinguished career, Ian McEwan has proven himself to be among the least narrowly confined artists imaginable—a kind of anti-owl poet. In just the years since his novel Atonement made him as famous here in the U.S. as he’d already been for decades in his native Britain, McEwan has written about a neurosurgeon, a newly married couple on a disastrous honeymoon, a Nobel-prize winning physicist, an MI5 intelligence agent, and a family court judge.

It isn’t just McEwan’s subject matter that varies widely. He has shown considerable formal range throughout his career. Reading McEwan, I am sometimes reminded of James Wood’s description of Philip Roth as a “stealth postmodernist.” McEwan shares Roth’s taste for metafictional narrative gestures that call into question the supposed reality of his texts, but like Roth, he uses these gestures not to undermine the resonance of his fictional worlds but to enrich it. He is one of those writers who is not called an experimentalist because his experiments always seem to come out right.

For all their variation, certain characteristics unify McEwan’s books and make him one of the few literary novelists whose fans wait with great impatience for another dose. One of these is their ingenious plotting. McEwan is above all else a wonderful story teller, a builder of suspense. Another is his prose, which is witty and urbane, generally fluid and unfussy, but capable of rising, when needed, to rhetorical heights and moments of great emotional power. Finally, there are a handful of themes that likewise unify his work. One of these is the theme of innocence or—to borrow the title of one of my favorite McEwan books—The Innocent—a theme McEwan has been playing with since his very first novel, The Cement Garden, in which a trio of orphans enact a kind of Freudian inversion of the Garden of Eden after their parents’ death. The common understanding of innocence is that it is a state of grace that we lose through experience of the world. McEwan’s work reverses this understanding. For McEwan, it is knowledge that confers grace, and the Innocent is an ironically sinister figure, capable of doing great harm in his ignorance. Proust said that the only true paradise is a paradise lost. McEwan might add that the only true paradise lost is the one we have squandered through our own innocent blundering. You can always tell in a McEwan novel when a character is about to make a mistake he will regret for the rest of his life—it is that moment when he feels most certain of his own righteousness. Those of you who have read Atonement or On Chesil Beach will know exactly what I mean here.

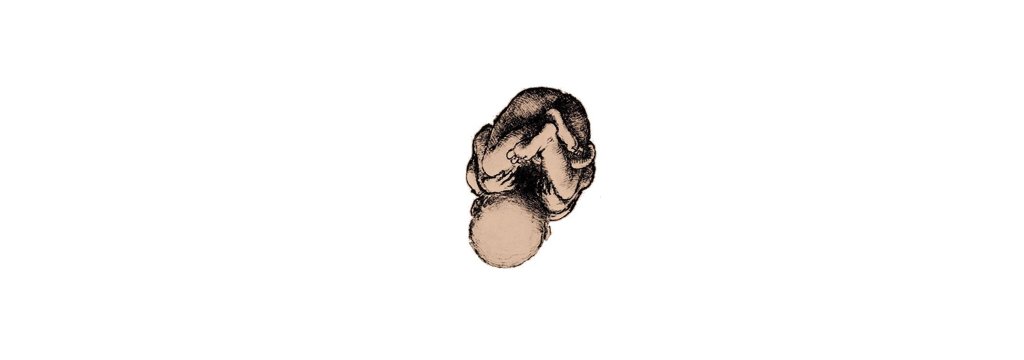

Given all this it feels almost inevitable in retrospect that Ian McEwan should write a novel from the perspective of that most exemplary figure of innocence—the unborn child. (Here the other shoe drops on the joke about artists in confined spaces.) And it feels particularly McEwan-esque that this fetal narrator should have such a knowing and sophisticated voice—more Humbert Humbert than Holden Caulfield—and that he should find himself, before even entering the world, implicated in a great crime. “I count myself an innocent,” he says at the beginning of the novel, “but it seems I’m party to a plot.” This may be Ian McEwan's definition of the human condition."

The novel’s title comes from Hamlet—“I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself king of infinite space”—as does the plot, which involves a mother named Trudie and an uncle named Claude—i.e., Gertrude and Claudius—planning the murder of the narrator’s father. Like Hamlet, our narrator is haunted by his own inability to act, though in fairness he has some constraints on his action that Hamlet didn’t. The resulting novel is—as I’ve already said—very funny. It’s also gripping and occasionally terrifying. In its premise and the extent of its intertextual playfulness it is, I think, like nothing McEwan has written before, and this may be finally what makes it a quintessential Ian McEwan novel. Here to read from Nutshell is Ian McEwan.

Selected Reviews and Criticism

Quinn, Annalisa. "A Bookish Mind At Play In 'Nutshell'." NPR.org, 14 September 2016. ["Nutshell is a joy: unexpected, self-aware, and pleasantly dense with plays on Shakespeare."]

Iaciofano, Carol. "Ian McEwan's Modern Hamlet Hears Everything -- From His Mother's Womb -- In Nutshell." WBUR.org, 13 September 2016.

Charles, Ron. "Ian McEwan’s Nutshell: A tale of betrayal and murder as told by a fetus." Washington Post, 12 September 2016. ["[A] story that’s surprisingly suspenseful, dazzlingly clever and gravely profound."]

Johnson, Carla K. "Nutshell Is Hamlet in Miniature." Washington Post, 12 September 2016. ["It takes a lion’s nerve to rewrite “Hamlet” from the viewpoint of a fetus, a stunt conceived and sweetly achieved by Ian McEwan in his latest novel, Nutshell."]

Donaldson, Emily. "Ian McEwan's Nutshell narrated, with great fun, by a fetus." Toronto Start, 11 September 2016.

Mukherjee, Siddhartha. "An Unborn Baby Overhears Plans for a Murder in Ian McEwan’s Latest Novel." New York Times, 9 September 2016. ["The writing is lean and muscular, often relentlessly gorgeous."]

Medley, Mark. "Ian McEwan feels ‘a sense of return’ with his new novel, Nutshell." Globe and Mail, 9 September 2016.

'Ian McEwan on His Novel Nutshell.' Guardian Podcast, 2 September 2016.

Miller, Michael W. 'Ian McEwan on Nutshell and Its Extraordinary Narrator.' Wall Street Journal, 29 August 2016.

Clanchy, Kate. "Nutshell by Ian McEwan review – an elegiac masterpiece." The Guardian, 27 August 2016. ["Nutshell is an orb, a Venetian glass paperweight, of a book; a place where – and be warned, it puts you in the quoting mood – Larkin’s 'any-angled light' may 'congregate endlessly'."]